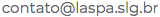

Associação diferencial (Sutherland)

=====================================================

UMA TEORIA DE CRIMINOLOGIA

SUTHERLAND, Edwin H. 1949. Uma teoria de Criminologia. In: Princípios de Criminologia. (trad. Asdrubal M. Gonçalves) São Paulo: Livraria Martins, pp.9-18. [1924]

O ACASO

O acaso não significa que não haja causas operando, mas sim que as causas são tão complicadas que não podem analisar-se. (Sutherland 1949:11)

PROCESSO DE ASSOCIAÇÃO

o comportamento crimisoso sistemático é determinado num processo de associação com aqueles que cometem crimes, exatamente como o comportamento legal sistemático é determinado num processo de associação com aqueles que são respeitadores da lei. (Sutherland 1949:12)

LOGO (generalizando para além da criminologia): Um comportamento sistemático é determinado num processo de associação com aqueles que praticam este comportamento sistemático.

O CRIME É A CAUSA DO CRIME (p.13)

ASSOCIAÇÃO DIFERENCIAL

Os princípios do processo de associação pelo qual se desenvolve o comportamento criminoso são os mesmos que os princípios do processo pelo qual se desenvolve o comportamento legal, mas os conteúdos dos padrões apresentados na associação diferem. Por essa razão, chama-se associação diferencial. (Sutherland 1949:13)

EXPERIÊNCIAS CRÍTICAS

É verdade, está claro, que uma única experiência crítica pode ser o ponto decisivo de uma carreira. Mas essas experiências críticas baseiam-se geralmente numa longa série de experiências anteriores e produzem em geral seus efeitos porque mudam as associações da pessoa. Uma das mais importantes dessas experiências críticas no determinar as carreiras criminosas é o primeiro aparecimento público como delinquente. O menino que é preso e condenado torna-se assim publicamente definido como criminoso. Desde então se restringem as suas associações com as pessoas que estão dentro da lei e ele se encontra lançado em associação com outros delinquentes. (Sutherland 1949:14-5)

CULTURA

A associação diferencial é possível porque a sociedade se compõe de vários grupos com culturas diversas. (Sutherland 1949:16)

=====================================================

A STATEMENT OF THE THEORY

SUTHERLAND, Edwin H. 1973. A statement of the theory. In: Karl Schuessler (ed.). Edwin H. Sutherland: on analyzing crime. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp.7-12. [1947]

THE PRINCIPLE OF DIFFERENTIAL ASSOCIATION:

A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable to violation of law. This is the principle of differential association. (Sutherland 1973:9)

QUANTIFICATION:

Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity. […] In a precise description of the criminal behavior of a person these modalities would be stated in quantitative form and a mathematical ratio be reached. A formula in this sense has not been developed, and the development of such a formula would be extremely difficult. (Sutherland 1973:9-10)

ASSOCIATION & SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

The person’s associations are determined in a general context of social organization. A child is ordinarily reared in a family; the place of residence of the family is determined largely by family income; and the delinquency rate is in many respects related to the rental value of the houses. Many other factors enter into this social organization, including many personal group relationships. (Sutherland 1973:11)

DISORGANIZATION x DIFFERENTIAL ORGANIZATION

The term “social disorganization” is not entirely satisfactory, and it seems preferable to substitute for it the term “differential social organization.” The postulate on which this theory is based, regardless of the name, is that crime is rooted in the social organization and is an expression of that social organization. A group may be organized for criminal behavior or organized against criminal behavior. Most communities are organized both for criminal and anti-criminal behavior, and in that sense the crime rate is an expression of the differential group organization. (Sutherland 1973:11)

=====================================================

DEVELOPMENT OF THE THEORY

SUTHERLAND, Edwin H. 1973. Development of the theory. In: Karl Schuessler (ed.). Edwin H. Sutherland: on analyzing crime. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp.13-29. [1942]

ABSTRACTING from CONCRETE CONDITIONS

Perhaps there is nothing that is so frequently associated with criminal behavior as being a male. But it is obvious that maleness does not explain criminal behavior. I reached the general conclusion that a concrete condition cannot be a cause of crime, and that the only way to get a causal explanation of criminal behavior is by abstracting from the varying concrete conditions things that are universally associated with crime. (Sutherland 1973:19)

DIFFERENTIAL ASSOCIATION & CULTURE CONFLICT

[D]ifferential association, is a statement of culture conflict from the point of view of the person who commits the crime. The two kinds of culture impinge on him or he has associations with the two kinds of culture, and this is differential association. (Sutherland 1973:20-1)

DIFFERENTIAL GROUP ORGANIZATION & DIFFERENTIAL ASSOCIATION

This concept [differential group organization] was designed to answer the question, Why does not criminal behavior, once initiated, increase indefinitely until everyone participates in it? The answer was: Several criminals perfect an organization and with organization their crimes increase in frequency and seriousness; in the course of time this arouses a narrower or a broader group which organizes itself against crime, and this tends to reduce crimes. The crime rate at a particular time is a resultant of these opposed organizations. Differential group organization, therefore, should explain the crime rate, while differential association should explain the criminal behavior of a person. The two explanations must be consistent with each other. (Sutherland 1973:21)

Dx/Dy (not neutral)

Actual participaion in criminal behavior is a resultant of two kinds of associations, criminal and anti-criminal, or the associations directed toward crime and the associations directed against crime. This eliminates a large portion of our experiences which are neutral so far as crime is concerned. [non-criminal culture] (Sutherland 1973:22)

CRIMINALS x CRIMINAL PATTERNS

[P]olicemen and prison guards seldom have intimate contact with criminals, and […] criminals have little prestige with these agents of justice. A policeman or a prison guard has his most frequent, intimate, and prestigious associations with others in the same occupation and with members of the police machine; and when he participates in criminal behavior, it is most frequently in graft, which he learns from these associates. No attempt has been made to measure these exponents of association, and this certainly must be done if the hypothesis is to be used extensively, or progressively. (Sutherland 1973:25)

PATTERNS OF CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR

It is possible that emotional disturbance was sinificant in the genesis of delinquant behavior only as it resulted in increasing the frequency and intimacy of associations with delinquent patterns or the prestige of those patterns, or in isolating the individual from the patterns of anti-criminal behavior. Whether this would provide a clear-cut distinction between the delinquents and the non-delinquents I do not know, but I suspect that it would make a more complete distinction than is made by emotional disturbance as such. (Sutherland 1973:28)

=====================================================

CRITIQUE OF THE THEORY

SUTHERLAND, Edwin H. 1973. Critique of the theory. In: Karl Schuessler (ed.). Edwin H. Sutherland: on analyzing crime. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp.30-41. [1944]

=====================================================

SUSCEPTIBILITY AND DIFFERENTIAL ASSOCIATION

SUTHERLAND, Edwin H. 1973. Susceptibility and differential association. In: Karl Schuessler (ed.). Edwin H. Sutherland: on analyzing crime. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp.42-3.

SUSCEPTIBILITY

There may be an advantage in analyzing susceptibility for it gives a basis for prediction. It may be possible to determine susceptibility by a test of some sort, in which case one would merely be describing the person’s history of differential associations in that form. Susceptibility and the frequency necessary to produce overt crime bear an inverse ratio to each other. (Sutherland 1973:42)

O LaSPA é sediado no Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas (

O LaSPA é sediado no Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas (