![Tarde’s idea of quantification (Latour 2015 [2010]) Tarde’s idea of quantification (Latour 2015 [2010])](https://www.laspa.slg.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/latour_post-1024x683.jpg)

Tarde’s idea of quantification (Latour 2015 [2010])

LATOUR, Bruno. 2010. Tarde’s idea of quantification. In Matei Candea (Ed.). The social after Gabriel Tarde: debates and assessments. London: Routledge, pp.145-62.

“CIÊNCIA” SIM, “NATURAL” NÃO, SOCIAL

What is so refreshing in Tarde (more than a century later!) is that he never doubted for a minute that it was possible to have a scientific sociology – or rather, an “ inter-psychology”, to use his term. And he espoused this position without ever believing that this should be done through a superficial imitation of the natural sciences. (Latour 2010:145-6)

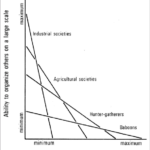

THE “LAW-STRUCTURE/INDIVIDUAL COMPONENTS” DISTINCTION IS THE RESULT OF A DEFICIT-LACK OF INFORMATION

Tarde’s reasoning goes straight to the heart of the matter: the natural sciences grasp their object from far away, and, so to speak, in bulk. […] It is therefore quite normal that they should rely on a rough outline of the “societies” of gas and cells to make their observations. (Remember that for Tarde “everything is a society.”) […] Although the very distinction between a law or structure and its individual components is acceptable in natural sciences, it cannot be used as a universal template to grasp all societies. The distinction is an artifact of distance, of where the observer is placed and of the number of entities they are considering at once. The gap between overall structure and underlying components is the symptom of a lack of information: the elements are too numerous, their exact whereabouts are unknown, there exist too many hiatus in their trajectories, and the ways in which they intermingle has not been grasped. It would therefore be very odd for what is originally a deficit of information to be turned into the universal goal of any scientific inquiry. (Latour 2010:148)

What is perfectly acceptable for “sociologists” of stars, atoms, cells and organisms, is inacceptable for the sociologists of the few billions of humans, or for the economists of a few millions of transactions. For in the latter cases, we most certainly have, or we should at least strive to possess, the information needed to dissolve the illusion of the structure. (Latour 2010:146)

Structure is what is imagined to fill the gaps when there is a deficit of information as to the ways any entity inherits from its predecessors and successors. (Latour 2010:153)

[T]he opposition is not between a holistic view of the societies […] and an individualist one. It is between a first approximation through crude statistical records that loses most of the inner quantification of the organism, and a more refined one that has learned how to follow how each of those organisms inherits and transmits its own individual innovations. Change the instruments, and you will change the entire social theory that goes with them. The only thing to lose is the notion of a structure, distinct from its incarnations, this artifact that compensates for a deficit of information. (Latour 2010:153)

TARDE (distinguia o estudo das sociedades humanas do estudo das outras pelos motivos certos, i.e.: pelo fato de que cientistas são humanos e, portanto, conhecem a sociedade “de dentro”) e DURKHEIM (fez a mesma coisa, mas pelos motivos errados, i.e.: petições de princípio, argumentos de autoridade, fórmulas retóricas como “pela força das coisas” etc.)

The shibboleth that distinguishes their [Tarde’s and Durkheim’s] attitudes is not that one is “for society” while the other is “for the individual actor.” (This is what the Durkheimians have quite successfully claimed so as to bury Tarde into the individual psychology he always rejected.) The distinction is drawn by whether one accepts or does not accept that a structure can be qualitatively distinct from its components. In response to this test question, Durkheim answers “yes” for both kinds of societies. Tarde says “yes”, for natural societies (for there is no way to do otherwise), but “no” for human societies. For human societies, and for only human societies, we can do so much more. (Latour 2010:147)

MONADOLOGY (desire/belief)

[F]or Tarde: the very heart of social phenomena is quantifiable because individual monads are constantly evaluating one another in simultaneous attempts to expand and to stabilize their worlds. The notion of expansion is coded for him in the word “desire,” and stabilization in the word “belief” […]. Each monad strives to possess one another. (Latour 2010:148)

How many entities can one entelechy reach? – That is desire. How many can they stabilize, order, fix or keep in place? – That is belief. No providence whatsoever can produce any harmony over and above the interplay of desire and belief in each monad, let loose on the world. […] With extreme avidity (a term Tarde prefers to that of ‘identity’), all monads will seize every possible occasion to grasp one another in a quantitative manner. This accelerates and also simplifies their aggregation and cohesion; it modifies them and gives them another turn and another handle. (Latour 2010:156)

A SOCIOLOGIA DE TARDE NÃO É BASEADA NO INDÍDUO PSICOLÓGICO, MAS NA INDIVIDUAÇÃO COLETIVA (TRANSINDIVIDUAL)

Does this mean that we should always stick to the individual? No, but we should find ways to gather the individual “he” and “she” without losing out on the specific ways in which they are able to mingle, in a standard, in a code, in a bundle of customs, in a scientific discipline, in a technology – but never in some overarching society. The challenge is to try to obtain their aggregation without either shifting our attention at any point to a whole, or changing modes of inquiry. […] Following the “imitative rays” will render the social traceable from beginning to end without limiting us to the individual, or

forcing a leap up to the level of a structure. (Latour 2010:149)

IMITAÇÃO como AÇÃO-REDE (ação distribuída, mas sempre local em cada ponto)

Imitation, that is, literally, the “epidemiology of ideas.” With this notion, he [Tarde] could render the social sciences scientific enough by following individual traits, yet without them getting confused when they aggregated to form seemingly “impersonal” models and transcendent structures. The term “imitation” may be replaced by many others (for instance, monad, actor-network or entelechy), provided these have the equivalent role: of tracing the ways in which individual monads conspire with one another without ever producing a structure. (Latour 2010:149)

O DUALISMO INDIVÍDUO/SOCIEDADE É O EFEITO DE UMA “TRANSIÇÃO DE FASE” (entre “individualizar um grupo” e “ser um indivíduo num coletivo”) AINDA MAL COMPREENDIDA

For Tarde, if we were to believe that the first duty of social science is to “reconcile the actor and the system” or to “solve the quandary of the individual versus society,” we would have to abandon all hope of ever being scientific. This is tantamount to aping the natural sciences, which are perfectly alright in getting by with discovering a structure and neglecting minor individual variations because they are much too far to observe whether or not a “collective self” emerges ex abrupto from “its astonished associates.” Fortunately, in the case of human sciences, we know this emergence is different. We can verify every day, alas, that “leaders” are “born from fathers and mothers” and not “collectively.” This forces us to discover the real conduits through which any group is able to emerge. For instance, we might search for how associates might “individualize in themselves the group in its entirety” through legal or political vehicles. Once we have ferreted out what makes this phase transition possible we will be able to see with clarity, the difference between “individualizing a group” and “being an individual in a collective structure.” Each case requires a completely different feel for the complex ecology of the situation. (Latour 2010:150)

AÇÃO-REDE (trajetória) PARA ALÉM DA OPOSIÇÃO INDIVÍDUO/SOCIEDADE (o agregado é real, mas nunca separado de suas variações individuais)

We have (or should have) full access to the aggregated dynamic. What is called a “structural law” by some sociologists is simply the phenomenon of aggregation: the formatting and standardization of a great number of copies, stabilized by imitation and made available in a new form, such as a code, a dictionary, an institution, or a custom. According to Tarde, if it is wrong to consider individual variations as though they were deviations from a law, it is equally wrong to consider individual variations as the only rich phenomenon to be studied by opposition with (or distance from) statistical results. It is in the nature of the individual agent to imitate others. What we observe either in individual variations or in aggregates are just two detectable moments along a trajectory drawn by the observer who is following the fate of any given “imitative ray.” To follow those rays (or “ actor-networks” […]) is to encounter, depending on the moment, individual innovations and then aggregates, followed afterwards by more individual innovations. It is the trajectory of what circulates that counts, not any of its provisional steps. (Latour 2010:151)

[T]he distinction between structure and ingredient […] [is] due to a deficiency of information. If the researcher is in possession of this information, this chain of invention, this “imitative ray,” then there is no reason why they cannot follow the individual innovation as well as the aggregates, smoothly. If there is a map of a river catchment, there is no need to leap from the individual rivulets to the River, with a capital R. We will follow, one by one, each individual rivulet until they become a river – with a small r. (Latour 2010:152)

COMO ACESSAR-CONSTRUIR CENTRAIS DE CÁLCULO

Here resides the fourth and final reason why Tarde’s sociology seems so original and so fresh for us today. A judgment of taste, an inflexion in the way we speak, a slight mutation in our habits, a preference between two goods, a decision taken on the spur of the moment, an idea flashing in the brain, the conclusion of a long series of inconclusive syllogisms, and so forth – what appears most qualitative is actually where the greatest numbers of calculations are being made among “desires” and “beliefs.” So, in principle, for Tarde, this is also the locus where we should be best able to quantify. Providing, that is, that we have the instruments to capture what he calls “logical duels.” (Latour 2010:154)

O INDIVÍDUO É UMA SOCIEDADE

The reason why there is no need for an overarching society is because there is no individual to begin with, or at least no individual atoms. The individual element is a monad, that is, a representation, a reflection, or an interiorization of a whole set of other elements borrowed from the world around it. If there is nothing especially structural in the “whole,” it is because of a vast crowd of elements already present in every single entity. This is where the word “network” – and even actor-network – captures what Tarde had to say much better than the word “individual.” Contrary to what is often said, there is not even a hint of “methodological individualism” in this argument. There is no psychologism, nor of course any temptation toward “rational choice.” (Latour 2010:154)

Behind every “he” and “she,” one could say, there are a vast number of other “he’s” and “she’s” to which they have been interrelated. When Tarde insists that we detect specific embranchments and bifurcations behind every innovation, he is not saying that we should celebrate individual genius. It is rather that geniuses are made of a vast crowd of neurons!. (Latour 2010:155)

A monarch is to his people what conscience is to the brain, what ego is to the neurons, what Darwin is to the thousands of naturalists through the obscure work on which he depends for his “glory”! Once again, the “one” piggybacks on top of the “many” but without composing a “they.” This is where Tarde’s originality resides: everything is individual and yet there is no individual in the etymological sense of that which cannot be further divided. (Latour 2010:155)

CIÊNCIA É SOBRE E NA NATUREZA

science is in and of the world it studies. It does not hang over the world from the outside. It has no privilege. This is precisely what makes science so immensely important: it performs the social together with all of the other actors, all of whom try to turn new instruments to their own benefits. (Latour 2010:156)

TARDE VISIONÁRIO

It is quite amusing to imagine Tarde directing his statistical bureau, nurturing so many doubts about the quality of the data he was handing out to the Ministry of Justice (and also to Marcel Mauss who was helping his uncle to write his book, Suicide, in which Tarde was trashed every two footnotes …), while dreaming, at the same time, of the many interesting quantitative instruments he had no way of obtaining: the “gloriometer” for following reputation (so easily accessible now with page rankings); conversation for understanding economic transactions (now the object of so many tools following buzz and viral marketing – Rosen 2009); “phonometers” like those invented by Abbé Rousselot in order to follow the smallest inflexions of the native speakers (now accessible through the automated study of vast corpora of documents). […] When Tarde claimed that statistics would one day be as easy to read as newspapers, he could not have anticipated that the newspapers themselves would be so transformed by digitalization that they would merge into the new domain of data visualization. This is a clear case of a social scientist being one century ahead of his time because he had anticipated a quality of connection and traceability necessary for good statistics which was totally unavailable in 1900. A century later, networks and traces are triggering the excitement of social and natural scientists everywhere (Barabasi 2003; Benkler 2006). […] Digital navigation through point-to-point datascapes might, a century later, vindicate Tarde’s insights. (Latour 2010:158)

O LaSPA é sediado no Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas (

O LaSPA é sediado no Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas (